How Carbon Positive Australia is restoring the Wheatbelt with nature positive planting

Did you know that Western Australia is home to some of the most biodiverse biospheres in the world? This beautiful state was largely uninterrupted for 270 million years, allowing time for a diverse range of flora and fauna to evolve, many of which are endemic to this corner of the world. Today, Western Australia has one of the worst deforestation rates in the world, and the Wheatbelt of WA is one of Australia’s most degraded land areas.

Did you know that Western Australia is home to some of the most biodiverse biospheres in the world? This beautiful state was largely uninterrupted for 270 million years, allowing time for a diverse range of flora and fauna to evolve, many of which are endemic to this corner of the world. Today, Western Australia has one of the worst deforestation rates in the world, and the Wheatbelt of WA is one of Australia’s most degraded land areas.

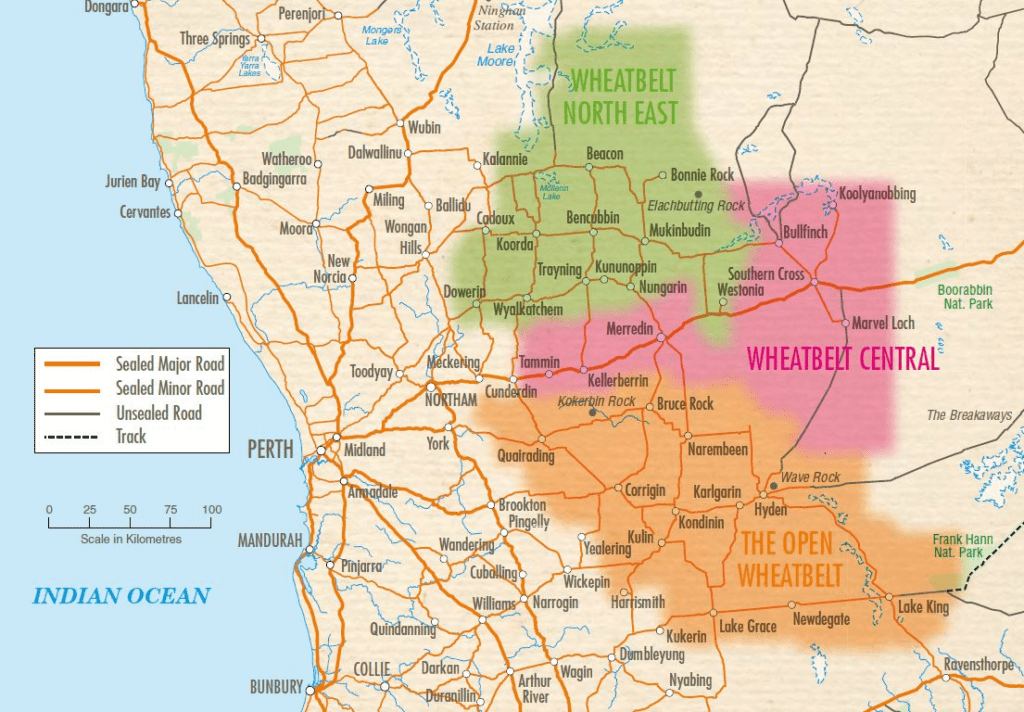

The Wheatbelt is one of WA’s nine geographic regions. It partially surrounds the Perth metropolitan area, extending north from Perth to the Mid-West region and east to the Goldfields-Esperance region. Bordered to the south by the South West and Great Southern regions and to the west by the Indian Ocean, the Perth metropolitan area, and the Peel region. Altogether, it has an area of 154,862 square kilometres.

The history of land clearing in the Wheatbelt

To understand how the land of the Wheatbelt became so degraded, we have to go back in time…all the way back to the 1890s (over 130 years ago) and why it was so attractive for clearing (that one is easy – it’s in the name).

Farms were established in the twentieth century to provide an independent living for hardworking families and grain for millions. A range of crops were grown in the Wheatbelt in addition to wheat that included:

• Coarse grains – barley, oats, sorghum, maize (i.e. corn), triticale, millets/panicums, cereal rye and canary seed;

• Oilseeds – canola (i.e. rape seed), sunflower, soybean, safflower and linseed;

• Pulses/legumes – lupins, field peas, chickpeas, faba beans, vetch, peanuts, mung beans, navy beans, pigeon peas.

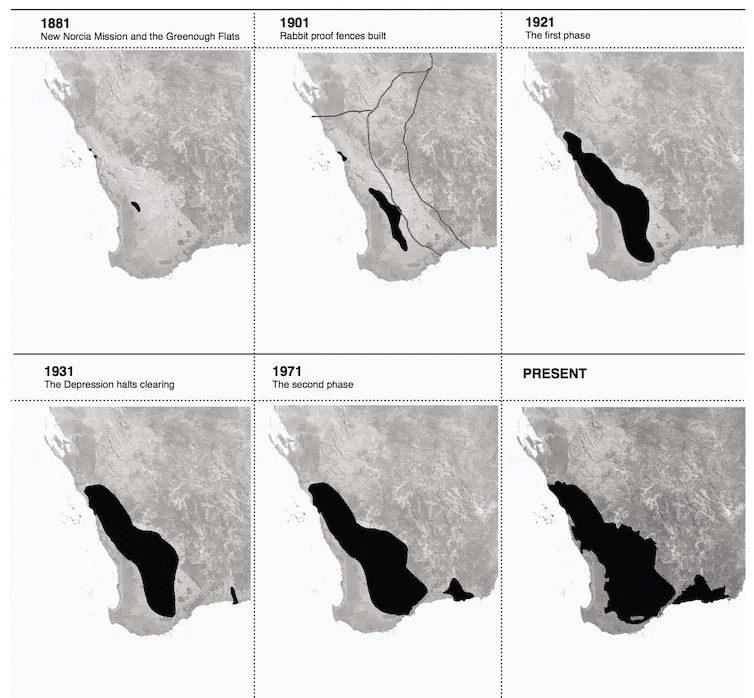

During the 1890s, broadscale vegetation removal began for the expansion of sheep and wheat industries. So began the loss of our biodiverse flora and fauna in what was once a diverse ecosystem. This continued into the twentieth century, gaining momentum after the Second World War. From 1946, bulldozers were used to push over trees, while crawler tractors dragging logs or chains would take out Mallee trees and low shrubs. (2)

In 1949, more than 6.48 million hectares of land was cleared for farming. By 1969 this area had more than doubled to 13.77 million hectares. While economic and climatic conditions were favourable, farming proceeded apace. But from 1969, drought and a glut of wheat on international markets, which led to the introduction of wheat quotas, together brought land releases to an abrupt halt. Farmers across the Wheatbelt, especially in the newly established areas, struggled throughout the 1970s.

Prior to clearing, the Wheatbelt consisted mainly of indigenous species such as Salmon Gum (Eucalyptus salmonophloia), York Gum (Eucalyptus loxophleba), and Wandoo (Eucalyptus wandoo) woodlands, heath thickets and scrub.

The loss we have seen over the years in the Wheatbelt is similar to other states but has one point of difference: most of this clearing happened in the mid-twentieth century.

The current state of the Wheatbelt

The clearing of the Wheatbelt has contributed to a decline in biodiversity and an increase in issues such as soil erosion and salinity. It has been noted by Journalist Andrea Gaynor that “The Wheatbelt was eaten as a result of an inappropriate vision for the region. This vision motivated prospective farmers and resourced them to cut, burn, plow, and sow the land, and indeed the climate had been transformed.”

The Wheatbelt is now home to 11% of Australia’s critically endangered plants. A number of critically endangered and threatened birds call the Wheatbelt their home, including the Carnaby’s Black Cockatoo and the Malleefowl.

What is Carbon Positive Australia’s approach to restoring the Wheatbelt?

At Carbon Positive Australia, we use nature as our guide to plant and deliver ecologically sensitive revegetation projects across WA, including the Wheatbelt region.

Each biodiverse restoration project we take on is tailored to its location through a detailed site assessment, species selection, and site preparation process. Site assessments provide valuable information regarding each site’s soil type, rainfall, and topography. A native reference site is also identified from surrounding bushland to aid species selection and provide a basis for monitoring project outcomes.

It is important that species selection is diverse and replicates the natural environment. Seed is often collected from remnant bush on the site to ensure species are native and adapted to local conditions. Site preparation often includes activities such as fencing, weed control, ripping, scalping, and mounding planting rows.

Once the site is prepared, planting can begin! We typically plant during winter to align with the highest available rainfall. We choose the planting method approach based on what is most suitable for the site. This may include direct-seeding, hand-planting seedlings, or a combination of both. Planting can take days, weeks, or even months, depending on the size and difficulty of the site.

After planting, we return to each site to undertake comprehensive monitoring assessments. This involves setting up permanent monitoring plots and recording the species, health, height, and pest damage of each seedling within each plot. This process is essential to track progress and determine whether infill planting is required in the following years.

While planting degraded land can be a challenging and often unpredictable process, it is one which is crucial to restoring health and biodiversity to the Wheatbelt. Key benefits include facilitating the return of native fauna, rehabilitating soil and waterways, and protecting native bushland for years to come, all of which are extremely rewarding for landholders, the community, and the environment.

In 2023, we will plant 170 hectares of land at a site near Warralakin in the Wheatbelt, Kalamaaya country. Located directly adjacent to Chiddarcooping Nature Reserve, this ecologically sensitive area is part of a larger property owned by Bush Blocks Guardians Inc. The planting site is located within a biodiversity hotspot and is home to several threatened flora and fauna species, including the Malleefowl.

Our aim is to restore native vegetation to the area, creating habitat to support a range of woodland species including Dunnarts, Western Yellow Robbins, Brushtail Possums, and Pink Cockatoos, who all call the Wheatbelt their home.

Stay tuned for more updates on this exciting project.

It is going to take effort from all of us to restore the Wheatbelt and this isn’t our first time planting here. Check out some of our previous Wheatbelt projects that include Bencubbin, Brookton Biodiverse, Brookton Saltland, Gabbin and Narrogin.

If you would like to help us continue our work in restoring Country, please consider making a donation here.

1. Wyalkatchem C.B.H Agricultural Museum, W.A.

2 How to Eat a Wilderness – Inside Story – Andrea Gaynor

• State Library of Western Australia

• Saunders DA. Changes in the avifauna of a region, district, and remnant as a result of fragmentation of native vegetation: the Wheatbelt of Western Australia. A case study, Biol Conserv, 1989, vol 50 (pg. 99-135)